Introduction to tom yaya kange

1. The highlands setting

Tom yaya kange are one of several regional genres of sung tales that are found in the highlands of Papua New Guinea. Map 1 shows the location of Papua New Guinea within the Asia-Pacific region. Note that the country called Papua New Guinea occupies only the eastern half of the Island of New Guinea. The western half is a part of Indonesia. Map 2 is a map of Papua New Guinea. In the middle of it you can see the Highland region where the genres of sung tales are found.

Map 1: Papua New Guinea within the Asia-Pacific region

Map 2: Papua New Guinea

The highlands region was one the last parts of New Guinea to come into contact with Europeans, starting in the 1930s. When that happened, it was a big surprise to both sides. Parts of New Guinea had already been colonised by Holland, Germany and Britain in the late nineteenth century, but until the 1930s the colonists thought that the highlands were unoccupied. When Australian gold prospectors first got there in 1932 they were astounded to find not only that there were people there, but that there were many of them. In the precolonial era, the central highlands were by far the most densely populated part of the island, and they remain the most densely populated part of Papua New Guinea, apart from the coastal cities of Port Moresby and Lae (where many Highlanders now live also). With its temperate climate, fertile soil and year-round growing season, the central highlands offers unusually good conditions for agriculture, and archaeology shows that it has been practiced there for at least 10,000 years, and quite intensively for at least 6000 years (Golson et al 2017).

The highlanders were even more surprised at the arrival of these strange light-skinned outsiders, about whom they had heard nothing before. Image 1 is a photo of one of those first encounters, with Australian gold prospector Michael Leahy, and image 2 is another one. Images 3, 4 and 5 are some colour photos taken about 25 years later in the Western Highlands at a large-scale ceremonial exchange event. On the ground in the second colour photo are specially mounted gold lip pearl shells, which were one of the two main traditional wealth objects in highlands, the other one being pigs.

The highlanders were even more surprised at the arrival of these strange light-skinned outsiders, about whom they had heard nothing before. Image 1 is a photo of one of those first encounters, with Australian gold prospector Michael Leahy, and image 2 is another one. Images 3, 4 and 5 are some colour photos taken about 25 years later in the Western Highlands at a large-scale ceremonial exchange event. On the ground in the second colour photo are specially mounted gold lip pearl shells, which were one of the two main traditional wealth objects in highlands, the other one being pigs.

Image 1: Michael Leahy meets New Guinea Highlanders

Image 2: Michael Leahy meets New Guinea Highlanders

Images 3, 4 and 5: Ceremonial exchange event

Verbal art is highly prized across the highlands region. Many people are very good story tellers there. In addition to ordinary storytelling, in some areas of the highlands there are genres of sung tales such as tom yaye kange, which are a high art that is practiced only by a few. Those areas are shown in purple on map 3. During 2003-2007, the wide range of sung-tale genres found within that region were the subject of a comparative research project led by linguistic anthropologist Alan Rumsey, in collaboration with ethnomusicologist Don Niles and twelve other researchers working in other language areas shown on the map–including New Guinean ones from the region. The project culminated in 2011 with the publication of a volume including studies by those researchers of all of the major regional genres of sung tales. The volume, with linked audio and video, is available on open access.

Map 3: Areas of the highlands where genres of sung tales such as tom yaye kange are found.

2. Tom Yaya kange

The tom yaya kange1 genre is the focus of this web site. This genre of sung tales is found near the southeastern corner of the map, within the Ku Waru dialect region as indicated there. In collaboration with Francesca Merlan, Alan Rumsey has been doing linguistic-anthropological research in that region since 1981. Although they recorded some sung tales in the early 1980s, Alan Rumsey's main research on them began in 1997. All five of the tom yaya tales included on this site were recorded in that year, two of them at Rumsey and Merlan’s main field base at Kailge, in the Western Nebilyer Valley, and the other three in the Ku Waru speaking part of the neighbouring Eastern Kaugel Valley, with whom people at Kailge have close relations, including extensive intermarriage. A list of publications on tom yaya kange that have resulted from that work is included on the site here.

Throughout the Ku Waru region, as in most other parts of the highlands, the local economy is still largely a subsistence one, based on the intensive cultivation of sweet potatoes, taro and a wide range of other crops. Most households nowadays also grow coffee, which is the main source of cash income. This is used largely to pay school fees—most children attend local schools through grade six—and for non-market based transactions such as bridewealth, compensation and ceremonial exchange.

Across the whole of this region, social life, including residence patterns, marriage, wealth exchange and warfare is still to a great extent organized in terms of socio-territorial units called talapi (“tribes”, “clans”, etc.), which range in size from a few dozen people to over 10,000. In the Ku Waru region as elsewhere in the central and western highlands, men and women formerly lived in separate houses, boys sleeping in their mother’s until they were about twelve years old, then moving into their father’s. This has changed over the last few generations—partly under the influence of Christian churches which are active throughout the region—but men and women still do much of their indoor socializing in separate ‘men’s houses’ (lku tapa) and ‘women’s houses’ (ab lku). Many of their working hours are also spent apart in more-or-less gender-specific tasks, men making the new gardens, building the houses, chopping the firewood; women growing and harvesting sweet potatoes, tending the pigs, cooking the everyday meals, etc.

A basic principle of Ku Waru social life is that people must marry outside of their own talapi (socio-territorial unit). Another is that marriage requires the groom and his family to make a sizeable payment of what is called ab kuime, ‘bridewealth’ to the bride’s family. Finding a wife is a demanding task for a young man and his close kin, as it requires them to assemble a bridewealth payment of, roughly, 8-16 pigs (more than are raised by most households in five years) and 4000-8000 dollars (well beyond most families’ total annual cash income; formerly this part of the payment consisted of gold-lipped pearl shells, then equally hard to attain). Given the continuing practice of polygyny (multiple wives for men who can afford it), marriageable women are in short supply relative to the number of men looking for them. Though she is not the only person involved in the decision as to whom she will marry, a young woman who is being courted is usually allowed a final power of veto in the matter, which she can exercise in the almost certain knowledge that other prospective suitors are waiting in the wings. The challenges this presents to a young man, and what Stewart and Strathern (2002:123) call the “romance of exogamy”, provide one of the main subjects of many tom yaya sung tales to be discussed below.

Throughout the Ku Waru region, as in most other parts of the highlands, the local economy is still largely a subsistence one, based on the intensive cultivation of sweet potatoes, taro and a wide range of other crops. Most households nowadays also grow coffee, which is the main source of cash income. This is used largely to pay school fees—most children attend local schools through grade six—and for non-market based transactions such as bridewealth, compensation and ceremonial exchange.

Across the whole of this region, social life, including residence patterns, marriage, wealth exchange and warfare is still to a great extent organized in terms of socio-territorial units called talapi (“tribes”, “clans”, etc.), which range in size from a few dozen people to over 10,000. In the Ku Waru region as elsewhere in the central and western highlands, men and women formerly lived in separate houses, boys sleeping in their mother’s until they were about twelve years old, then moving into their father’s. This has changed over the last few generations—partly under the influence of Christian churches which are active throughout the region—but men and women still do much of their indoor socializing in separate ‘men’s houses’ (lku tapa) and ‘women’s houses’ (ab lku). Many of their working hours are also spent apart in more-or-less gender-specific tasks, men making the new gardens, building the houses, chopping the firewood; women growing and harvesting sweet potatoes, tending the pigs, cooking the everyday meals, etc.

A basic principle of Ku Waru social life is that people must marry outside of their own talapi (socio-territorial unit). Another is that marriage requires the groom and his family to make a sizeable payment of what is called ab kuime, ‘bridewealth’ to the bride’s family. Finding a wife is a demanding task for a young man and his close kin, as it requires them to assemble a bridewealth payment of, roughly, 8-16 pigs (more than are raised by most households in five years) and 4000-8000 dollars (well beyond most families’ total annual cash income; formerly this part of the payment consisted of gold-lipped pearl shells, then equally hard to attain). Given the continuing practice of polygyny (multiple wives for men who can afford it), marriageable women are in short supply relative to the number of men looking for them. Though she is not the only person involved in the decision as to whom she will marry, a young woman who is being courted is usually allowed a final power of veto in the matter, which she can exercise in the almost certain knowledge that other prospective suitors are waiting in the wings. The challenges this presents to a young man, and what Stewart and Strathern (2002:123) call the “romance of exogamy”, provide one of the main subjects of many tom yaya sung tales to be discussed below.

As we will see below in section 3, even within the Ku Waru region, there are considerable differences of style among performers. But all of their performances have certain features in common. These include the following2:

1)

They are performed solo, that is, by a single singer, without instrumental accompaniment.

2)

The wordings are not repeated verbatim from one performance to the next in the way that the lyrics in Ku Waru songs are. Rather, they vary across performances. In that respect the sung tales are more like spoken stories than songs. But they differ from spoken stories in making far more use of set phrases or ‘formulas’, as we will see below.

3)

Clear division into audibly distinct lines of matching length, each ending in an added vowel a or e, which has no specific lexical or grammatical meaning, but serves to mark the line off as such, and the speech variety as non-ordinary.

4)

The use of repeated set phrases or ‘formulas’, many of them belonging to a common stock of such phrases.

5)

Although sung tales are melodic, the tempo of sung-tale performances is faster than of songs–more like that of speech.

6)

The plots almost always involve a journey, usually by a young man who is on a mission of some sort. He meets with various obstacles along the way, sometimes successfully overcoming them and sometimes not.

7)

The language that is used in the sung tales differs in some ways from everyday speech and spoken story-telling.

8)

Extensive use of parallelism–the ordered interplay of repetition and variation.

9)

In common with spoken tales (called simply kange), tom yaya kange (sung tales) are considered by Ku Waru people to be, above all, a form of entertainment, to be enjoyed by men, woman and children of all ages, usually at home, often after the evening meal, rather than in large public spaces.

3. Examples of tom yaya kange performances and their poetic and musical features

As a first example of tom yaya kange, we invite the reader to watch a video of the opening lines of a performance by Peter Kerua that was recorded in 1997 (although not included in full on this site). Peter is the young man sitting in the middle. The story he sings is about a beautiful young woman named Wapi, who is courted by young men from all the surrounding tribes. She rejects all of them. Then one day while she is out working in the sweet potato garden, in the distance she hears enchanting music being played on a flute. She asks her friends who is playing it and they tell her it is a young man named Kubu Suwal from Kailge. She goes to Kailge in search of him. When she finds him there the two of them are immediately smitten with each other, embrace and decide to get married.

As you can see from the freeze-frame at the beginning of the video, everyone looks very serious. But after Kerua begins singing his tale you can see how their faces brighten up. Notice also how Kerua moves his head from side to side as he sings, often with his eyes shut, and sometimes looking upward as if in a kind of reverie. These movements and expressions are all typical of tom yaya performances, as is the sitting position, with audience members positioned close to the performer, who sometimes reaches out to touch them, as Kerua did later on in this performance.

Now let’s consider the opening lines of a tom yaya sung tale by another performer named Paulus Konts. Image 6 is a picture of Konts in his everyday clothes. And image 7 is a picture of him dressed up for performance at a sung tales workshop that we held in 2004. The full version of Konts’s tale is available on this site here. Like Peter Kerua’s tale in the video, Konts’s tale is about courtship, but with a different plot, which is actually a more standard one in this region. The male protagonist is a young man who, as we learn only halfway through the story, is Konts himself. One day Konts sees smoke billowing around a distant mountain from the fires that had been lit by a woman called Ayamp. Konts dresses up splendidly, takes his flute and jaw harp, and heads off to court her. He makes the long trek to Mount Ambra where she lives. She immediately becomes enamored of him, invites him to spend the night with her in her house, and next day agrees to marry him. Together they walk back to Konts’s home at Ambukl. Konts's parents are delighted, and they prepare a huge bridewealth payment of pigs and money which they invite Tangapa's family to come and receive. Konts and Tangapa get married and produce children and grandchildren as numerous as the toes on a litter of piglets3.

Now let’s consider the opening lines of a tom yaya sung tale by another performer named Paulus Konts. Image 6 is a picture of Konts in his everyday clothes. And image 7 is a picture of him dressed up for performance at a sung tales workshop that we held in 2004. The full version of Konts’s tale is available on this site here. Like Peter Kerua’s tale in the video, Konts’s tale is about courtship, but with a different plot, which is actually a more standard one in this region. The male protagonist is a young man who, as we learn only halfway through the story, is Konts himself. One day Konts sees smoke billowing around a distant mountain from the fires that had been lit by a woman called Ayamp. Konts dresses up splendidly, takes his flute and jaw harp, and heads off to court her. He makes the long trek to Mount Ambra where she lives. She immediately becomes enamored of him, invites him to spend the night with her in her house, and next day agrees to marry him. Together they walk back to Konts’s home at Ambukl. Konts's parents are delighted, and they prepare a huge bridewealth payment of pigs and money which they invite Tangapa's family to come and receive. Konts and Tangapa get married and produce children and grandchildren as numerous as the toes on a litter of piglets3.

Image 6: Paulus Konts in 2004, on stage for performance at the Goroka Sung Tales Workshop, photo by Don Niles

Image 7: Paulus Konts in 1997, photo by Alan Rumsey

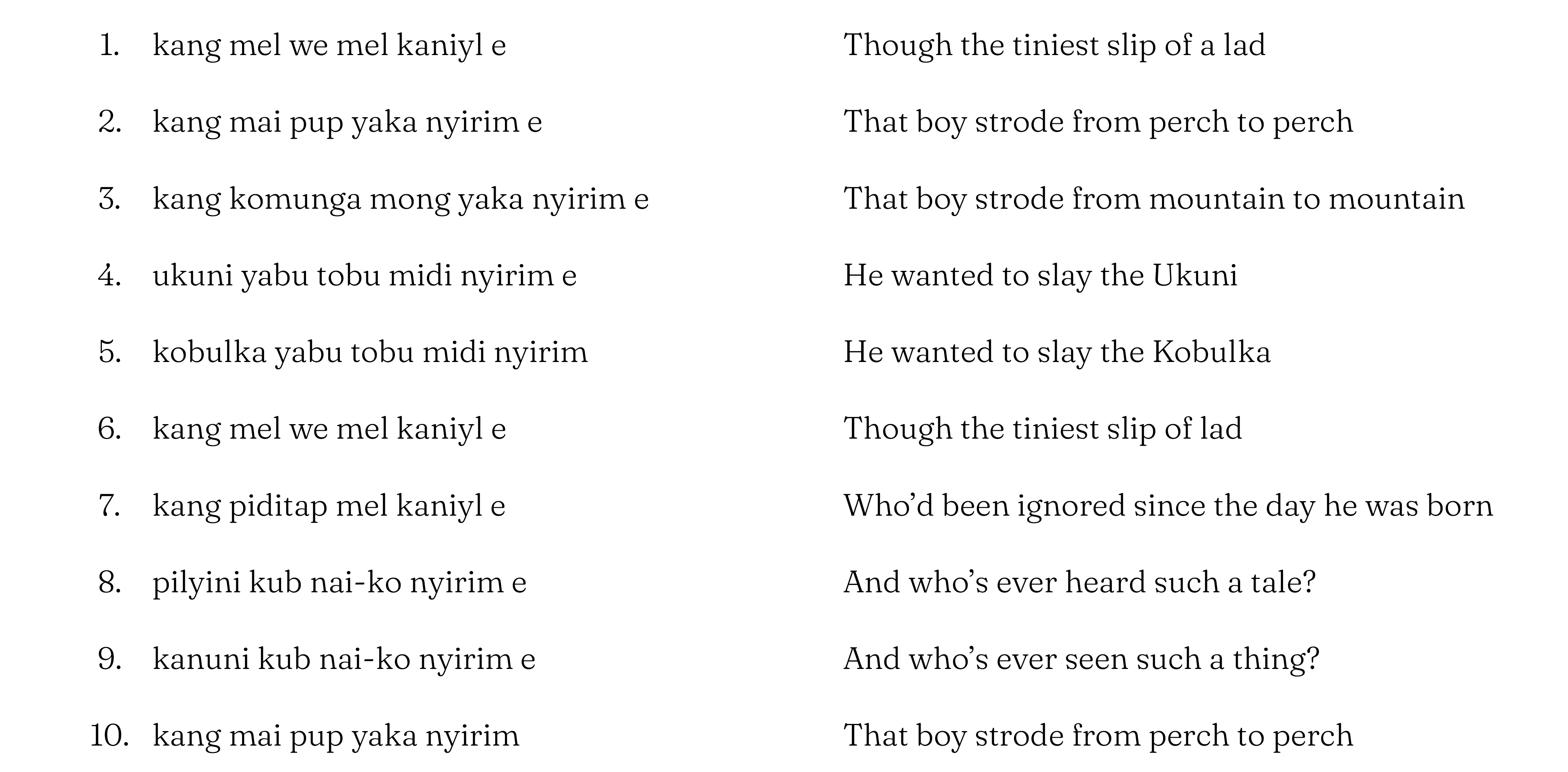

Now let us consider the first sixteen lines of Kont’s performance, as shown in text 14. The places where Konts takes a breath are marked by a comma. Before playing the audio, the reader should be aware that the text is sung to a melody that is sounded within the first eight lines and then repeated within the next eight lines. The transition between those two soundings of the melody is shown by an extra space after line 8.

Text 1: Opening lines of a tom yaya kange in five-beat style by Paulus Konts

Note the following points in regard to Text 1:

1)

The text is divided into lines of equal length.

2)

Each line ends in an added vowel, e or a which has no lexical or grammatical meaning, but serves to mark the line off as such.

3)

Each line has five beats.

4)

Each beat corresponds to a single word or to the added vowel at the end of the line.

As pointed out above, the text is sung to a repeating, eight-line melody, with the transition between them shown in the space between lines 8 and 9. As can be heard by listening to longer stretches of the full tale here and following them in the transcript here, the same eight-line melody is repeated throughout the 1065-line performance.

Before considering the melody let us look at the text and see how it exemplifies a feature which is found in all tom yaya performances, as in many forms of verbal art around the world: parallelism5– the ordered interplay of repetition and variation. Here again are the first 9 lines of Konts’s sung tale, with two color-coded instances of parallelism:

Before considering the melody let us look at the text and see how it exemplifies a feature which is found in all tom yaya performances, as in many forms of verbal art around the world: parallelism5– the ordered interplay of repetition and variation. Here again are the first 9 lines of Konts’s sung tale, with two color-coded instances of parallelism:

Text 2: Instances of parallelism in text 1.

The first instance of parallelism can be seen in lines 2 and 3, and the second in lines 8 and 9. In each case some of the words are repeated from one line to the next and some of them change from line to line. The ones that change are highlighted in green and the ones that remain the same are in yellow. As in all cases of poetic parallelism, the repetition of some elements establishes a ground against which a salient relationship is indicated between the elements that change. In lines 2 and 3 the relevant relationship is one of contrast, between everyday attire made of banana leaves and special, more decorative attire made from cordyline leaves. In lines 8 and 9 the relevant relation is one of complementarity, between two musical instruments that are both used in courting.

Another feature of this text that is typical of tom yaya kange as in many genres of ‘oral epic’ around the world (Reichl 2000, Lord 1960) is the use of repeating, set phrases, or ‘formulas’. Examples are highlighted in blue in the text 3, again showing the first 16 lines of Konts’s performance. Not only is there repetition between lines 4 and 15, each of the highlighted expressions is repeated many other times within the performance. Note that this repetition of individual formulas does not entail repetition of the entire text: no two performances of a given tale, even by the same performer, are ever exactly the same in their wording across the whole performance.

Another feature of this text that is typical of tom yaya kange as in many genres of ‘oral epic’ around the world (Reichl 2000, Lord 1960) is the use of repeating, set phrases, or ‘formulas’. Examples are highlighted in blue in the text 3, again showing the first 16 lines of Konts’s performance. Not only is there repetition between lines 4 and 15, each of the highlighted expressions is repeated many other times within the performance. Note that this repetition of individual formulas does not entail repetition of the entire text: no two performances of a given tale, even by the same performer, are ever exactly the same in their wording across the whole performance.

Text 3: Instances of parallelism in text 1.

Turning now from textual features of Konts’s tom yaya kange to its musical ones, in order to help the reader become more familiar with the melody, and see how the words and lines fit into it, Figure 1 is a representation of that melody in cypher notation. Each number corresponds to a step on the musical scale, with roughly the same pitch intervals as in the western major scale. We encourage the reader to listen again to the first 16 lines of Konts’s performance here, and try to follow them in figure 1, listening for the five beats in each line, the pitch movements as shown by the numbers, the vowels at end of each line (in the rightmost column), the breaths that Konts takes after lines 4, 8, 12, and 16, and the repetition of the melody that begins after the eighth line at the bottom of the figure.

Figure 1: Basic form of Konts’s 8-line tom yaya melody

Figure 2 shows the same melody in standard musical notation. Here, each line of the text corresponds to one measure in the melody. As with the cypher notation, this is not a transcription of any particular performance, but rather, a more abstract representation that shows the general form of the melody. Showing it in this form allows us to see more clearly that the melody consists of two parts, the second of which is a partial repetition of the first. This is shown by the dashed lines that indicate which of the notes repeat across the two parts and which of them do not.

Figure 2: Basic form of Konts’s 8-line tom yaya melody

This pattern of repetition and variation is the musical equivalent of the relation of parallelism that has been exemplified above as a feature of the texts of songs and sung tales. To see the similarity between musical and verbal parallelism compare the musical notation in figure 2 with the first example of verbal parallelism from text 2, which is repeated here:

Figure 2: Basic form of Konts’s 8-line tom yaya melody

In both the musical example and the textual one, some of the elements in the first line are repeated in the second line and some are changed–in both cases establishing a framework of coherence that binds the two lines together as parts of a larger whole.

Before moving on to the work of another performer from the Ku Waru region, it is important to note an interesting thing about how Paulus Konts learned to compose and perform sung tales. As background for this, there are two things to point out. One is that, in addition to the differences among regional styles of sung tales that have been referred to in table 1, within each of the regions there are also considerable differences among individual performers. At least within the Ku Waru and Melpa regions that am familiar with, people say that each performer has his own personal style.

The other thing I want to point out is that in the late 1970s and early 1980s the radio broadcasts of the Papua New Guinea National Broadcasting featured a considerable amount of local content, including story-telling and singing in the local languages. In the Mount Hagen area in 1980 there were broadcasts of a sung tale by a performer from the Melpa region named Paul Pepa. Pepa was 21 years old at the time. Image 8 is a picture of him that was taken 34 years later at the first sung tale workshop that we held in 2004.

Before moving on to the work of another performer from the Ku Waru region, it is important to note an interesting thing about how Paulus Konts learned to compose and perform sung tales. As background for this, there are two things to point out. One is that, in addition to the differences among regional styles of sung tales that have been referred to in table 1, within each of the regions there are also considerable differences among individual performers. At least within the Ku Waru and Melpa regions that am familiar with, people say that each performer has his own personal style.

The other thing I want to point out is that in the late 1970s and early 1980s the radio broadcasts of the Papua New Guinea National Broadcasting featured a considerable amount of local content, including story-telling and singing in the local languages. In the Mount Hagen area in 1980 there were broadcasts of a sung tale by a performer from the Melpa region named Paul Pepa. Pepa was 21 years old at the time. Image 8 is a picture of him that was taken 34 years later at the first sung tale workshop that we held in 2004.

Image 8: Paul Pepa in 2004, on stage for performance at the Goroka Sung Tales Workshop, Photo by Don Niles

In the intervening years, that 1980 recording and the figure of Paul Pepa had become renowned throughout the Western Highlands Province for his skilfulness and distinctive style. The performance became known, not only through the radio broadcast, but also through cassette recordings of it that were made by people who listened to it and recorded it on their radio-cassette recorders. In that way, unlike in the face-to-face settings through which the tales had previously been exclusively propagated, Pepa’s performance became well-known to many people who had never met him. One of them was Paulus Konts, whose performance of another tale I have discussed above. When my musicologist colleague Don Niles and I obtained a copy of Pepa’s 1980 recording and listened closely to it, we realized it that had a five-beat line and exactly the same 8-line melody that Konts uses, which is different from that of any other performer I recorded in the Ku Waru region. When we asked Konts about this he readily acknowledged that he had learned to compose sung tales entirely from listening to the broadcast recording of Paul Pepa.

An interesting difference is that Pepa’s performance was in the Melpa language, whereas Konts’ native language is Ku Waru. The areas associated with those languages can be seen in the southwestern corner of map 3 (see map 3 above). With respect to his understanding of Pepa’s text, that difference presented no problem for Konts, who is bilingual in Melpa and Ku Waru, as are many people in the Ku Waru region. The two languages are about as different as Spanish and Italian. But putting the tale into Ku Waru would still have required considerable ingenuity from Konts in order for him to fit his Ku Waru wordings within the same five-beat line structure as Pepa’s. In this and other ways, to say that Konts learned his sung-tale style from Pepa is not to say that he simply repeats Pepa’s tales. Rather, he uses the same five-beat line and eight-line melody that Pepa did, but to perform many different tales, including some that are traditional ones, and many that are his own creations, sometimes even casting himself as the main character in them as in the tale of his that I have discussed.

The first time that Pepa and Konts met each other in person was during the preparations for our 2004 workshop. Image 9 is a photo of them on the day they first met, at a boarding house in Mt Hagen, to which I had brought them on our way to Goroka where the workshop was held.

An interesting difference is that Pepa’s performance was in the Melpa language, whereas Konts’ native language is Ku Waru. The areas associated with those languages can be seen in the southwestern corner of map 3 (see map 3 above). With respect to his understanding of Pepa’s text, that difference presented no problem for Konts, who is bilingual in Melpa and Ku Waru, as are many people in the Ku Waru region. The two languages are about as different as Spanish and Italian. But putting the tale into Ku Waru would still have required considerable ingenuity from Konts in order for him to fit his Ku Waru wordings within the same five-beat line structure as Pepa’s. In this and other ways, to say that Konts learned his sung-tale style from Pepa is not to say that he simply repeats Pepa’s tales. Rather, he uses the same five-beat line and eight-line melody that Pepa did, but to perform many different tales, including some that are traditional ones, and many that are his own creations, sometimes even casting himself as the main character in them as in the tale of his that I have discussed.

The first time that Pepa and Konts met each other in person was during the preparations for our 2004 workshop. Image 9 is a photo of them on the day they first met, at a boarding house in Mt Hagen, to which I had brought them on our way to Goroka where the workshop was held.

Image 9: Paul Pepa (left) and Paulus Konts (right) at their first meeting, in Mount Hagen, 2004, Photo by Alan Rumsey

As noted above, and as can be heard from listening again to Peter Kerua’s performance and Kont’s, they sound very different from each other. As another example of stylistic diversity within the Ku Waru region, I now turn to the work of another performer named Noma Guraiya. Image 10 is a photo of him, taken in 1981, in Francesca’s and my house at Kailge, listening to a recording I had made of one of his speeches.

Image 10: Noma Guraiya listening to one of his speeches in 1981, Photo by Alan Rumsey

Noma was already alive when the first outsiders arrived from Australia in 1932, and had a lot of interaction with them from an early age, learning the lingua franca Tok Pisin and working as a translator. For many years after Papua New Guinea became independent in 1975 Noma held the elected office of Village Councillor, as you can see from the badge he is wearing in the photo. In addition to his role for the government he was also a leading singer and composer of songs, and practitioner of the traditional oratorical genre, of which he is listening to one of his performances in the picture6.

Noma was also a highly skilled performer of sung tales. His style is like Konts’s in having a fixed number of beats per line and a repeating melody with a fixed number of lines, but it differs from Konts’s in the number of beats and lines. Before I get into those details, I invite the reader to listen to this recording of the opening lines of one of Noma’s sung-tale performances (one that is included in full on this site here, along with the full text, translation and synopsis here). The tale is about a small boy who leaves his adoptive parents to go out and fight with their tribe’s traditional enemies, and in the process discovers who his true parents are and settles down to live with them.

Noma was also a highly skilled performer of sung tales. His style is like Konts’s in having a fixed number of beats per line and a repeating melody with a fixed number of lines, but it differs from Konts’s in the number of beats and lines. Before I get into those details, I invite the reader to listen to this recording of the opening lines of one of Noma’s sung-tale performances (one that is included in full on this site here, along with the full text, translation and synopsis here). The tale is about a small boy who leaves his adoptive parents to go out and fight with their tribe’s traditional enemies, and in the process discovers who his true parents are and settles down to live with them.

Text 4: Text of the first ten lines tom yaya sung-tale performance by Noma Guraiya

As can be heard from the recording, Noma’s tale has a fixed number of beats per line, but with six beats instead of five as in the Konts/Pepa style that is exemplified by text 1. A related difference is that almost all of Noma’s lines have one more word in them than do Konts’s. This is consistent with a generalisation I made above about text 1, that each beat within it corresponds to a single word or to the added vowel at the end of the line. A slight difference in Noma’s performance is that, where he pauses to take a breath, as shown by the commas at the lines 6 and 10, there is no added vowel. The breath-pause itself is treated as a final beat in the line, whereas in Konts’s performance, the breaths (at the ends of lines 5 and 8 in text 1), do not displace the line-final vowel, but combine with it to comprise a single beat.

In addition to its longer line, Noma’s tom yaya tale has a longer melody. This is shown in figure 3, which is a musical transcription of the ten lines shown in text 4. As in the musical notation of Konts’s melody in figure 2, here each line the text corresponds to one measure in the melody.

In addition to its longer line, Noma’s tom yaya tale has a longer melody. This is shown in figure 3, which is a musical transcription of the ten lines shown in text 4. As in the musical notation of Konts’s melody in figure 2, here each line the text corresponds to one measure in the melody.

Figure 3: Musical transcription of the first ten lines tom yaya sung-tale performance by Kopia Noma

As can be seen from the transcription, there are ten measures in Noma’s melody. While it differs in that respect from Konts’s eight-measure melody, in another way it is similar. Like Konts’s melody Noma’s has two parts, the second of which is a partial repetition of the first. This can be seen in figure 3 by comparing measure 1 with measure 6, measure 2 with line 7, 3 with 8, 4 with 9 and 5 with 10. In each case, just as in Konts’s melody shown in figure 1, some of the notes in corresponding positions across the two paired measures are the same and others are different. For example, the first three notes in line 1 are the same as the first three notes in line 6, whereas the pitches in the rest of each of those lines are slightly different. Likewise, the last four notes in line 5 are the same as those of line 10, whereas the other notes are different.

In his very thorough PhD thesis on the full range of musical genres in this region, Don Niles (2007) has shown that the melodies in almost all of them have a similar two-part structure, in which some of the notes in the first half are repeated within corresponding positions in the second half and some are different. And again, as in the case of Konts’s tom yaya kange, we can see the relevant relations of parallelism that are evident in the melody of the same general form as those in the text, involving what I have described as an ‘ordered interplay of repetition and variation’.

As I noted above when discussing Noma’s tom yaya kange, and as shown by the commas in Figure 3, Noma takes a breath at the end of lines 5 and 10. Now that we have considered Noma’s melody, in which each line of text 3 maps onto one musical measure, it can be seen that those breaths come at the end first half of the melody and at the end of the second half, just as we have seen above for Konts, who takes a breath always and only at the end of the each half of the melody. Remarkably, Konts kept that pattern up throughout his performance, which lasted 20 minutes and contained 1065 lines, and Noma kept it up through almost all of his performance, even though he was a much older man at the time, with less lung power. That kind of amazing breath control by both of these men is just one of reasons why they are/were identified as virtuoso performers of tom yaya sung tales.

As I have pointed out above in relation to Kont’s sung tale, in addition to the sonic parallelism that is found in the two-part melodies in this region, there is also extensive parallelism in the poetic lines of the sung tales. This is also true of Noma’s performance. Here are some instances of it in the first ten lines:

In his very thorough PhD thesis on the full range of musical genres in this region, Don Niles (2007) has shown that the melodies in almost all of them have a similar two-part structure, in which some of the notes in the first half are repeated within corresponding positions in the second half and some are different. And again, as in the case of Konts’s tom yaya kange, we can see the relevant relations of parallelism that are evident in the melody of the same general form as those in the text, involving what I have described as an ‘ordered interplay of repetition and variation’.

As I noted above when discussing Noma’s tom yaya kange, and as shown by the commas in Figure 3, Noma takes a breath at the end of lines 5 and 10. Now that we have considered Noma’s melody, in which each line of text 3 maps onto one musical measure, it can be seen that those breaths come at the end first half of the melody and at the end of the second half, just as we have seen above for Konts, who takes a breath always and only at the end of the each half of the melody. Remarkably, Konts kept that pattern up throughout his performance, which lasted 20 minutes and contained 1065 lines, and Noma kept it up through almost all of his performance, even though he was a much older man at the time, with less lung power. That kind of amazing breath control by both of these men is just one of reasons why they are/were identified as virtuoso performers of tom yaya sung tales.

As I have pointed out above in relation to Kont’s sung tale, in addition to the sonic parallelism that is found in the two-part melodies in this region, there is also extensive parallelism in the poetic lines of the sung tales. This is also true of Noma’s performance. Here are some instances of it in the first ten lines:

Text 5: Instances of parallelism in text 4.

Turning now to another poetic feature of Noma’s performance, in section 2, I pointed out above that across the entire sung-tales region the language used in the sung tales is different from that in everyday speech. In the case of the Ku Waru region as shown on the map, one of the main differences is that the syntax of everyday language is greatly simplified in order to fit the words into the short poetic lines in terms of which the sung tales are musically organised. The syntax of everyday speech in Ku Waru is very complex, especially in narrative discourse, making much use of long strings of dependent verbs and clauses. An example can be seen in figure 4, which shows a Chinese-box-like, syntactically analysed excerpt from a spoken version by Kopia Noma of the same story about a small boy that he performed in the sung version that is discussed above7.

In Ku Waru as in many other New Guinea languages, the verb in a clause or sentence always comes last. Clauses are often strung together into long sentences which describe a sequence of actions. There is a basic distinction in the language between verb forms that can only come at the end of a sentence and others that cannot come at the end, but can occur only in one of the previous clauses within the sentence. The final verb is the only one that is marked for tense. All of the verbs in the preceding clauses depend on that final verb for their tense marking.

In Ku Waru as in many other New Guinea languages, the verb in a clause or sentence always comes last. Clauses are often strung together into long sentences which describe a sequence of actions. There is a basic distinction in the language between verb forms that can only come at the end of a sentence and others that cannot come at the end, but can occur only in one of the previous clauses within the sentence. The final verb is the only one that is marked for tense. All of the verbs in the preceding clauses depend on that final verb for their tense marking.

Figure 4: Syntactically analysed excerpt from spoken tale by Noma Guraiya

The whole passage shown in figure 4 comprises a single sentence. The only part of it that could alternatively stand alone as an independent sentence is the last two words wed urum ‘She came there’. The final verb in it, urum, is in the remote past tense, which is used for events that happened at least two days ago. All the other verbs in the sentence depend on that final verb in order to be interpreted as referring to events that happened in the remote past.

Now let us look at how Noma refers to those same events in his sung version of the story (the full version of which is available on this site here):

Now let us look at how Noma refers to those same events in his sung version of the story (the full version of which is available on this site here):

Text 6: Excerpt from tom yaya kange by Noma Guraiya, narrating the same events as his prose version in Figure 4

In this sung version of the story the same sequence of events as in the figure 4 is musically narrated, not in one long sentence but in five much shorter ones, each of which ends with a final verb, and is independently marked for remote past tense. Furthermore, each of those sentences is fit into a single line or short sequence of lines, and each sentence ends at the end of a line, never within a line. In short, the complex syntax of the spoken version is greatly simplified in order to adapt the story to the poetic and rhythmic structure of Noma’s repeating six-beat line. The same is true of Kont’s sung tale as discussed above, and all the other 18 performances of tom yaya sung tales that I have recorded and analysed.

What is gained by this simplification of the syntax is the creation of a set of building blocks that allow enhanced possibilities for musical and poetic parallelism. This can seen by looking again at the examples of parallelism from the first ten lines of Noma’s sung tale:

What is gained by this simplification of the syntax is the creation of a set of building blocks that allow enhanced possibilities for musical and poetic parallelism. This can seen by looking again at the examples of parallelism from the first ten lines of Noma’s sung tale:

Text 5: Instances of parallelism in text 4.

In this version of the transcript as above, I have separated each pair of lines in which there are parallel terms. As you can see, in each case the parallel terms occur in positions that match from one line to the next. In this way, the alignment of syntactic structure with sung lines of constant length creates conditions for parallelism that would not be possible in more complex forms of narrative speech such the example shown in figure 4. That is crucial to the poetic form of tom yaya kange, because parallelism is pervasive in them. That is by no means unusual in comparative terms: parallelism is a widely attested and much-studied feature in genres of verbal art around the world (e.g., Jakobson 1960, Fox 1988, Fabb 1997). What has been less extensively studied are the ways in which everyday speech is modified in order to facilitate parallelism. In Ku Waru this is done above all through the shaping of speech into short lines of constant length which fit with the syntactic structure of the sung text.

4. Concluding remarks

This paper opened with an introduction to the Papua New Guinea highlands, with particular focus on the Ku Waru region where tom yaya sung tales are found. That was followed by a brief overview of the tom yaya genre, and examination of excerpts from three tom yaya performances, each by a different bard. On that basis I discussed and exemplified a number of the main textual and musical features of the genre, and differences between individual performers with respect to line structure and melody. The excerpts discussed in most detail were from two performances for which the full recordings and texts are available on this site, along with plot summaries and details about the performers. Drawing on what you have learned from this introduction, we hope you will go on to explore and appreciate those performances much more fully, and the other four tales on this site, as marvelous examples of the cultural riches and diversity that can be found among indigenous peoples of the world–in this case, in the highlands of Papua New Guinea.

Notes

1. The phrase ‘tom yaya kange’ can be roughly translated as ‘loud praise tale’. Since kange means ‘tale’, when referring to the genre in English, elsewhere in this introduction and site we will omit it and refer simply to ‘tom yaya tale(s)’

2. All of these features are in fact common to all genres of sung tales across the wider region shown on map 3 (see map 3 above). For discussion of other features which differ across that wider region see Rumsey (2005), Rumsey (2017), Niles and Rumsey (2011).

3. For a more detailed plot summary of this tale look here.

4. As can be seen in the full transcript of this performance and heard in the full audio recording of it, the performance begins with two introductory lines that fall outside of the repeating melody in terms of which the rest of the performance is organized. They have been omitted here to make it easier to hear the melody.

5. For wide-ranging comparative discussions of parallelism, see Jakobson 1960, Fox 1988 and Fabb 1997.

6. For a more detailed life story and character sketch of Noma, see Rumsey (2006:332-334).

7. The abbreviations used in figure 4 show the grammatical categories in the Ku Waru words above them. The categories are: COM comitative, DEF definite, FUT future, NF non-final, PPL participle, pl plural, sg singular, 3 third person. These labels have been included for the sake of completeness but you don’t have understand them in order to understand the main point of this example, which is that its syntax is very complex, as shown by the multiple brackets within brackets, displaying the Chinese-box-like structure of syntactic units with units, etc. For anyone interested in learning more about Ku Waru grammar and how such labelled categories are used in it, see Merlan and Rumsey 1991: 322-343.

4. Concluding remarks

This paper opened with an introduction to the Papua New Guinea highlands, with particular focus on the Ku Waru region where tom yaya sung tales are found. That was followed by a brief overview of the tom yaya genre, and examination of excerpts from three tom yaya performances, each by a different bard. On that basis I discussed and exemplified a number of the main textual and musical features of the genre, and differences between individual performers with respect to line structure and melody. The excerpts discussed in most detail were from two performances for which the full recordings and texts are available on this site, along with plot summaries and details about the performers. Drawing on what you have learned from this introduction, we hope you will go on to explore and appreciate those performances much more fully, and the other four tales on this site, as marvelous examples of the cultural riches and diversity that can be found among indigenous peoples of the world–in this case, in the highlands of Papua New Guinea.

Notes

1. The phrase ‘tom yaya kange’ can be roughly translated as ‘loud praise tale’. Since kange means ‘tale’, when referring to the genre in English, elsewhere in this introduction and site we will omit it and refer simply to ‘tom yaya tale(s)’

2. All of these features are in fact common to all genres of sung tales across the wider region shown on map 3 (see map 3 above). For discussion of other features which differ across that wider region see Rumsey (2005), Rumsey (2017), Niles and Rumsey (2011).

3. For a more detailed plot summary of this tale look here.

4. As can be seen in the full transcript of this performance and heard in the full audio recording of it, the performance begins with two introductory lines that fall outside of the repeating melody in terms of which the rest of the performance is organized. They have been omitted here to make it easier to hear the melody.

5. For wide-ranging comparative discussions of parallelism, see Jakobson 1960, Fox 1988 and Fabb 1997.

6. For a more detailed life story and character sketch of Noma, see Rumsey (2006:332-334).

7. The abbreviations used in figure 4 show the grammatical categories in the Ku Waru words above them. The categories are: COM comitative, DEF definite, FUT future, NF non-final, PPL participle, pl plural, sg singular, 3 third person. These labels have been included for the sake of completeness but you don’t have understand them in order to understand the main point of this example, which is that its syntax is very complex, as shown by the multiple brackets within brackets, displaying the Chinese-box-like structure of syntactic units with units, etc. For anyone interested in learning more about Ku Waru grammar and how such labelled categories are used in it, see Merlan and Rumsey 1991: 322-343.